Of the 2,400 species of bromeliads distributed across the world, at least 400 species are tank bromeliads.

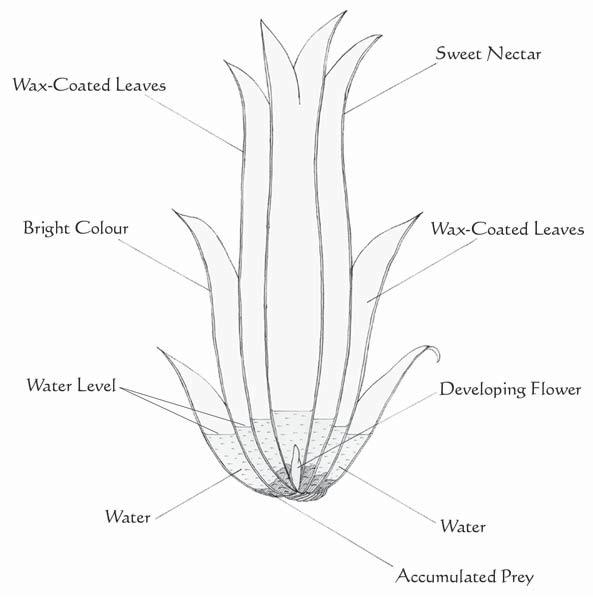

The tank bromeliads are distinguished in that they produce foliage that is arranged as a watertight leaf rosette adapted to collecting and storing rain and organic debris to provide a source of water and nutrients. In most cases, the foliage of tank bromeliads has hollow leaf axils in which water can collect however in a few species, the foliage is tightly arranged to form a tube and water collects only in the center of the leaf rosette.

This arrangement of the leaves enables rainwater to collect and be stored efficiently to the extent that largest species of tank bromeliads can individually store several litres of water for use when rains fail. This is beneficial for the tank bromeliads since all species of tank bromeliads occur in tropical and subtropical latitudes of the American continents. Even though in most cases, these plants receive high levels of precipitation in their natural habitats for much of the year, tropical sunlight is intense and often continual for several hours each day and can causes rapid rates of evaporation and transpiration of water. Tank bromeliads, with their permanent supply of stored water are therefore far less prone to drying out, especially during ‘dry seasons’ or times when rains fail, during which regular bromeliad plants may perish.

The storage of rainwater in the wells of tank bromeliads also brings about the advantage that nutrients naturally accumulate. Falling leaf litter, waste produces from birds and flying insects and the general fallout of dust and other organic particles rains down continually and collects in the wells of the tank bromeliads. Dissolved in the rainwater which the tank bromeliads also collect, the accumulated organic material breaks down and naturally releases essential nutrients and minerals into the water within the tank bromeliads wells. Since the leaves of all tank bromeliads are naturally lined with modified hair-like structures called trichomes which enable the absorption of water and nutrients directly into the plants leaves, the tank bromeliads can directly make use of the organic material which they collect. This is particularly important since the majority of tank bromeliads grow as epiphytes on the branches of trees, independent from nutrients in the substrate in the ground. This ability of tank bromeliads to augment nutrients from debris that accumulates in their water reservoirs enables these plants to grow vigorously independently from their surroundings and consequently, tank bromeliads are often most numerous and most prolific in the most barren and hospitable of habitats where few regular plants without such adaptations can survive.

The ability of tank bromeliads to collect nutrients is not just restricted to the accumulation of debris within the wells of these plants. Many tank bromeliads have evolved complex partnerships and relationships with a variety of animals, especially amphibians and arthropods. A wide variety of frogs and insects lay their eggs within the leaf wells of the tank bromeliads. Each well of water within the tank bromeliads rosette can therefore exist as a miniature community of microbes, bacteria and protozoa which are the food for a range of minute crustaceans which in terms are food for insect larvae (especially mosquito larvae) which serve as food for frog large and large arthropod larvae such as juvenile dragonflies. That the water catchments of the tank bromeliad serves as a nurseries for various animals brings about further nutrient inputs as eggs are laid and in the case of some frogs, food is actively brought to feed tadpoles. These inputs all bring about further nutrients which the tank bromeliads can absorb. The delicate balance and suite of dependent animal species – the so called ‘infauna – can vary dramatically between each species of tank bromeliad however is often remarkably complex and dynamic. However the abundance of animal life within the water reservoirs of tank bromeliads is advantageous from the perspective of the tank bromeliads since the fauna serves to break down collected organic debris (such as leaf litter) and release into the water nutrients which the plant can then absorb.

In a few cases, plants have also evolved to exploit the bountiful supply of nutrients in the wells of the tank bromeliads. In South America, a carnivorous plant called Utricularia humboldtii has specialized to grow almost exclusively in the water filled reservoirs of a large tank bromeliad called Brocchinia tatei. Utricularia humboldtii traps prey by use of 3 – 7 mm long hollow, white ‘bladder’ which are produced sporadically along the length of the plant’s filamentous stem. Each bladder has a small hinged door on its forward side which is fringed with minute trigger hairs. Glands on the interior surface of the bladder remove water and air so that the internal pressure is appreciably lower than that of the exterior. If a microscopic organism touches the trigger hairs, the small trapdoor implodes inwards and through the inward rush, the small victim is swept inside. Once prey is caught, the trapdoor swiftly closes and the imprisoned victim soon perishes and enzymes released by glands on the interior of the bladder quickly digest the soft remains of the victim’s body and resultant dissolved nutrients are absorbed through the walls of the bladder. Through this elaborate trapping process, Utricularia humboldtii traps microscopic prey in the wells of Brocchinia tatei plants and grows continually by producing tendrils which search few the wells of the tank bromeliad.

An Utricularia humboldtii plant (with a purple flower) growing and hunting in the leaves of a Brocchinia tatei plant

Despite the presence of plants such as Utricularia humboldtii, the quantity of nutrients which tank bromeliads can derive from their water reservoirs is very significant and indeed the plants can be extremely successful within particular niche habitats. As a result, species of tank bromeliads have evolved to grow both terrestrially (on the ground) and epiphytically (on the branches of trees) and in some cases carpet the landscape flourishing in habitats where competing regular plant species cannot survive. Indeed in many cases, tank bromeliads (especially of the genus Brocchinia) can be found growing directly on bare rock in areas where no substrate is present.

The exact structure and shape of tank bromeliads varies profoundly between genera and species, however most form broad, expansive leaf rosettes because such a structure affords the most efficient collection of organic debris and rain water. Perhaps for a similar reason, tank bromeliads can reach spectacular sizes, several species of the genus Brocchinia produce spectacular foliage in excess of one meter in length (so that the entire leaf rosette can exceed two meters in diameter) and in some species, the foliage grows atop of a woody trunk like stem which can eventually grow to a meter or more in height.

While most species of tank bromeliads naturally produce leaves that are yellow or green, some particularly desirable species and artificially produced hybrids and cultivars produce spectacular red, purple or patterned foliage. The often bright colouration of the tank bromeliads makes them very desirable and beautiful plants to grow in cultivation, and in most cases, tank bromeliads are very easy to grow providing that their water reservoirs are always kept full with water.

Full information on the cultivation of tank bromeliads and nurseries where they can be purchases is provided on the web site of the Bromeliad Society International, please see http://bsi.org for more details.

Stewart McPherson